Yes to catalogs

Publishing's surprisingly resilient piece of mail

The news that Amazon is sending print catalogs through conventional mail has one observer noting that “everything old is new again.” Maybe. But I’m prompted to acknowledge, warmly, my colleagues in publishing who never stopped—who designed, printed, and mailed catalogs through all the changes of the past couple of decades. There was resistance; I know from experience.

A lot of this has to do with the semi-mysterious world of reps. As the intermediaries who sell books to outlets (like bookstores) that help make titles available to readers, sales reps perform one of publishing’s key functions. And the catalog listing a publisher’s upcoming releases was traditionally seen primarily as the reps’ tool, something for them to share with their accounts.

That rationale began to change when new digital innovations (notably the platform Edelweiss) empowered sales reps to customize the material they shared, eliminating—many believed—the need for traditional print catalogs designed by publishers. A rep who might once have brought the whole seasonal catalog to a bookstore specializing in mysteries could now pluck just the records for mysteries. In ongoing negotiations over how to allocate money and time, the results were predictable. Chatter about how the reps no longer needed the catalog meant a lot of publishing houses stopped doing them.

Except I think the reasoning that “catalogs are for the reps” was wrong, or at least incomplete. In a digital world where everything’s available to shuffle and remix, the great strength of the catalog is that it’s linear. It’s a story. A publisher without a catalog misses an opportunity to tell the world about itself.

I’ll go further: the catalog is also a place where publishers describe themselves to themselves. Without the semi-annual opportunity to back up and have conversations about which books to emphasize, which blurbs to amplify, what bells and whistles to add, and how the whole thing should be curated and organized and made to look, publishers risk becoming muddled about the narrative around their work.

Put slightly differently, branding can be an exercise led by outsiders, complete with box lunch. Or it can be something more organic, driven by publishing workers’ healthy back-and-forth over the press’s sense of self. At the houses where I’ve worked, planning the catalog offered that chance to figure out what we wanted to say, not just about individual books but about the larger whole.

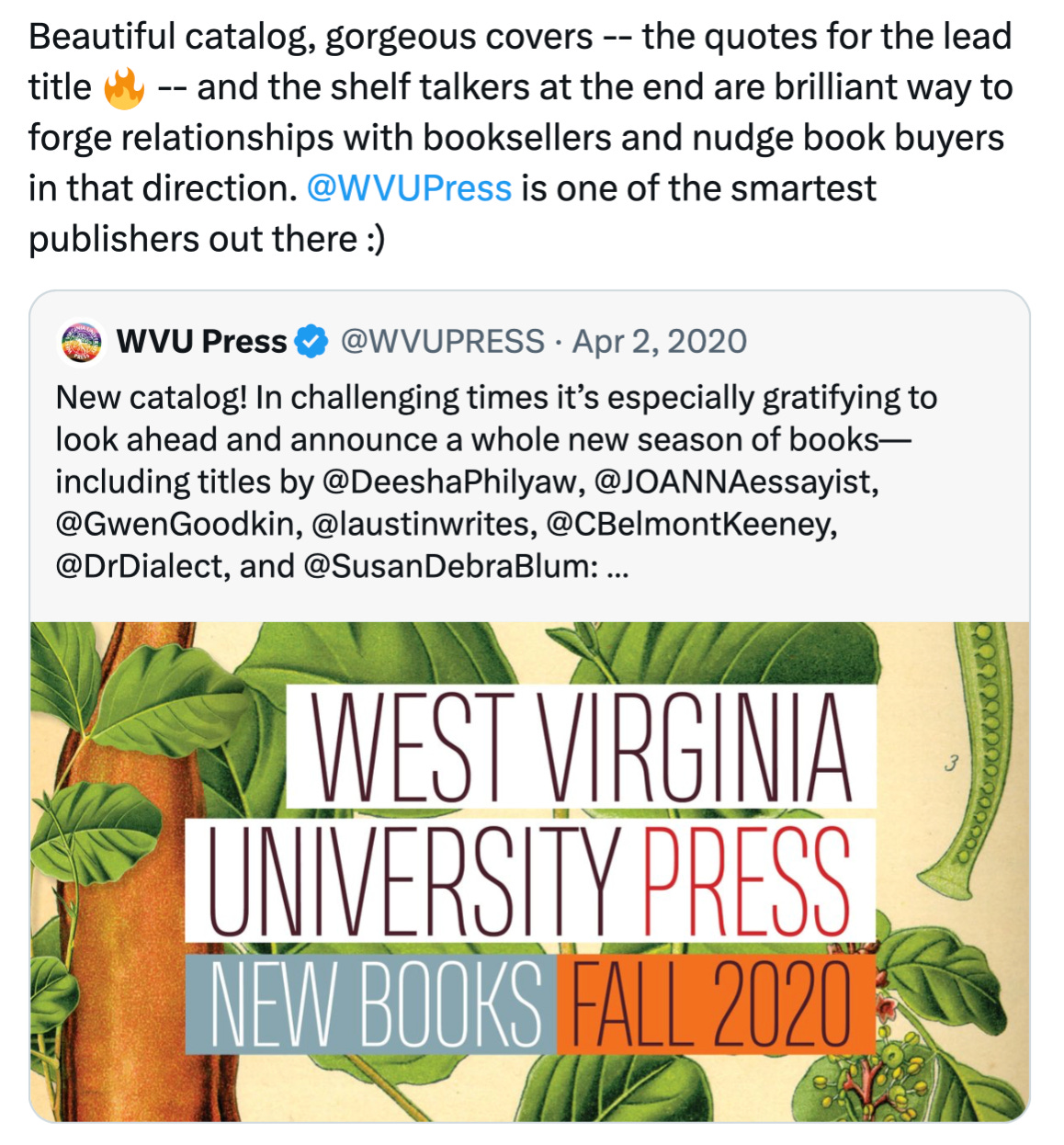

The growth of social media has only raised the stakes, in my experience. Less a replacement for physical documents like catalogs than an opportunity to amplify them, I’ve seen social media provide a platform for posts lauding publishers’ catalogs. These bits of affection may come from authors, colleagues, and booksellers, but I also see them from individual readers. At my last in-house position, we did an especially popular catalog during the early-pandemic lockdown, and people were writing in social-media comments to ask for a hard copy just to have as a keepsake.

Inviting readers into a relationship with the people who make their books feels beneficial to the whole ecosystem, and in my experience the catalog often feels like a prominent way to achieve that sense of connection, especially when combined with opportunities for online engagement.

I’ll close with links to a handful of recent pieces. I like this New York Times profile of Hagfish, a scrappy house that will, among other accomplishments, reissue Joan Silber’s early novel In the City. Also in the Times, Margaret Renkl—who reliably uses her high-profile perch to monitor bookish developments away from the coasts—tells a survival story about Humanities Tennessee and the Southern Festival of Books. And here on Substack, Fisher the Bookseller looks at who decides what goes on bookstore shelves, complete with reference to how Edelweiss eclipsed traditional catalogs in bookstores’ workflow.

This is a wonderful piece, Derek. Catalog as narrative : an easily underappreciated element in the cocktail we call publishing.

But is it a catalog or a catalogue? As the compilers of book and manuscript catalogues (UK), we encounter this question whenever we write about what we do or correspond with librarians and archivists. The only safe rule is to use the -og when corresponding with people in the US. But what to do about Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders? Do they -og or -ogue? The standard reference books seem to be silent on this question.