One place to find loads of working people with degrees in the humanities is book publishing, a field where (unlike, say, academic library work) no professional program or certification is typically required.

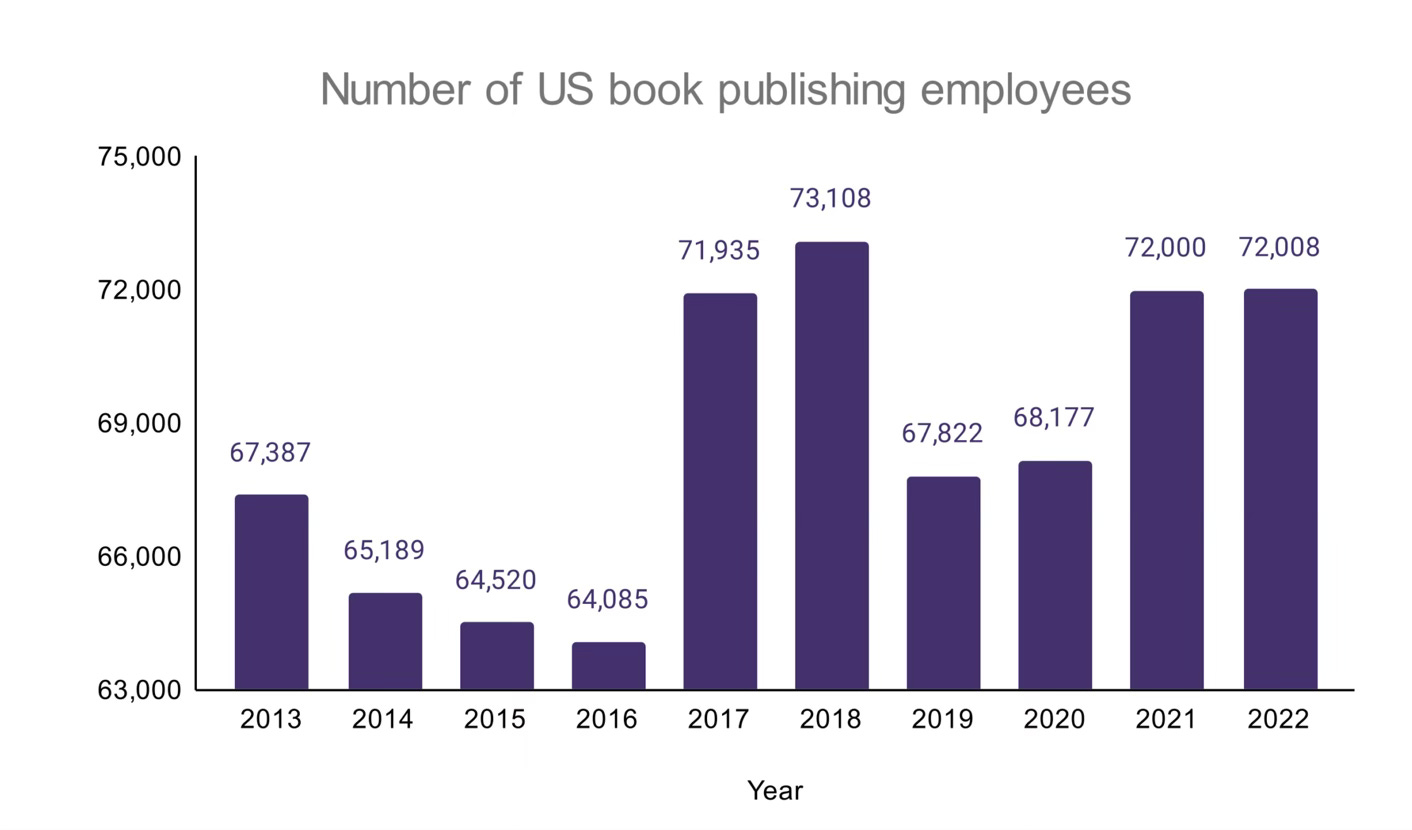

And there’s good news: The number of workers in US book publishing has held pretty steady—and is up since the start of the pandemic.

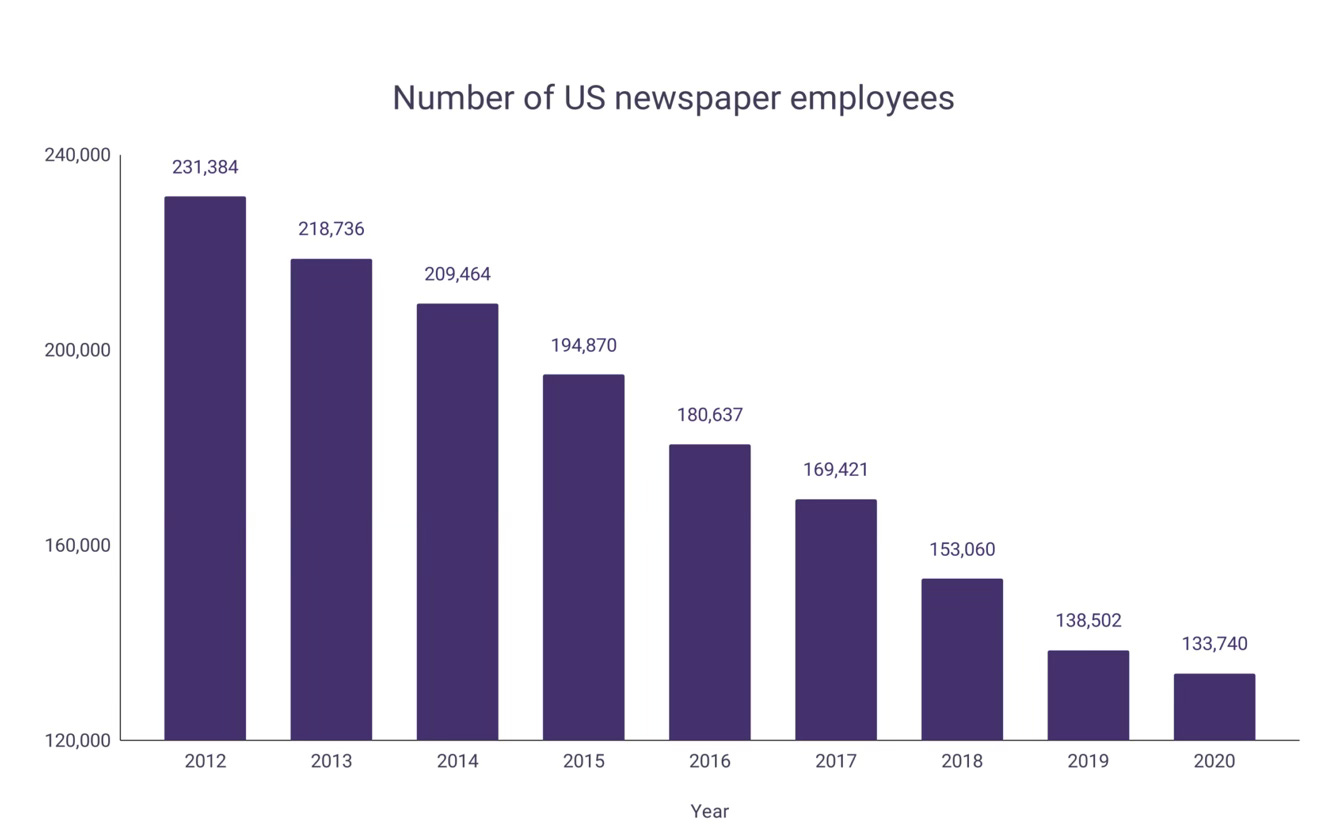

Compare that with trends in, for instance, the number of people working in newspapers, and it’s no wonder that other varieties of publishing see books as the standout success of the twenty-first century—the one form of media that hasn’t slipped into unpaywalled expectations of “free,” with all the associated revenue problems that make it so hard to, you know, pay people. (Franklin Foer treats this dynamic well in World Without Mind.)

I think this comparatively happy state of affairs should inspire vigilance. Employment opportunities in publishing need not just to exist but to pay well, and to offer dignity and security, especially if they’re going to attract workers from a diversity of backgrounds. New labor activism among publishing workers is a positive sign in this regard.

For university presses (the part of publishing where I have most experience), growth in job opportunities feels especially important, since these are, after all, publishers charged with advancing the public good. And I wonder here about the infusion of philanthropic and association money going to the promotion of Open Access—millions of dollars being pumped into the system to encourage a shift in business models so that readers, libraries, and other consumers of books aren’t the ones paying for them. What sorts of new jobs, if any, are these new infusions of resources enabling? (I genuinely don’t know and hope it’s being studied.) What if resources were focused instead on growing publishing’s professional opportunities?

Here’s a moonshot that excites me more than Open Access: Ten thousand new jobs in book publishing, to be staffed overwhelmingly by humanists. There’s plenty at stake, I think. When you center labor in considerations of books and publishing, you see all sorts of spillover effects—including the potential for expanded support to liberal arts programs. Liberal arts grads are many of books’ readers and most of their makers, and they deserve to be nurtured in ever more robust iterations of higher education’s humanities programs. Our fates as publishers and educators are entwined.