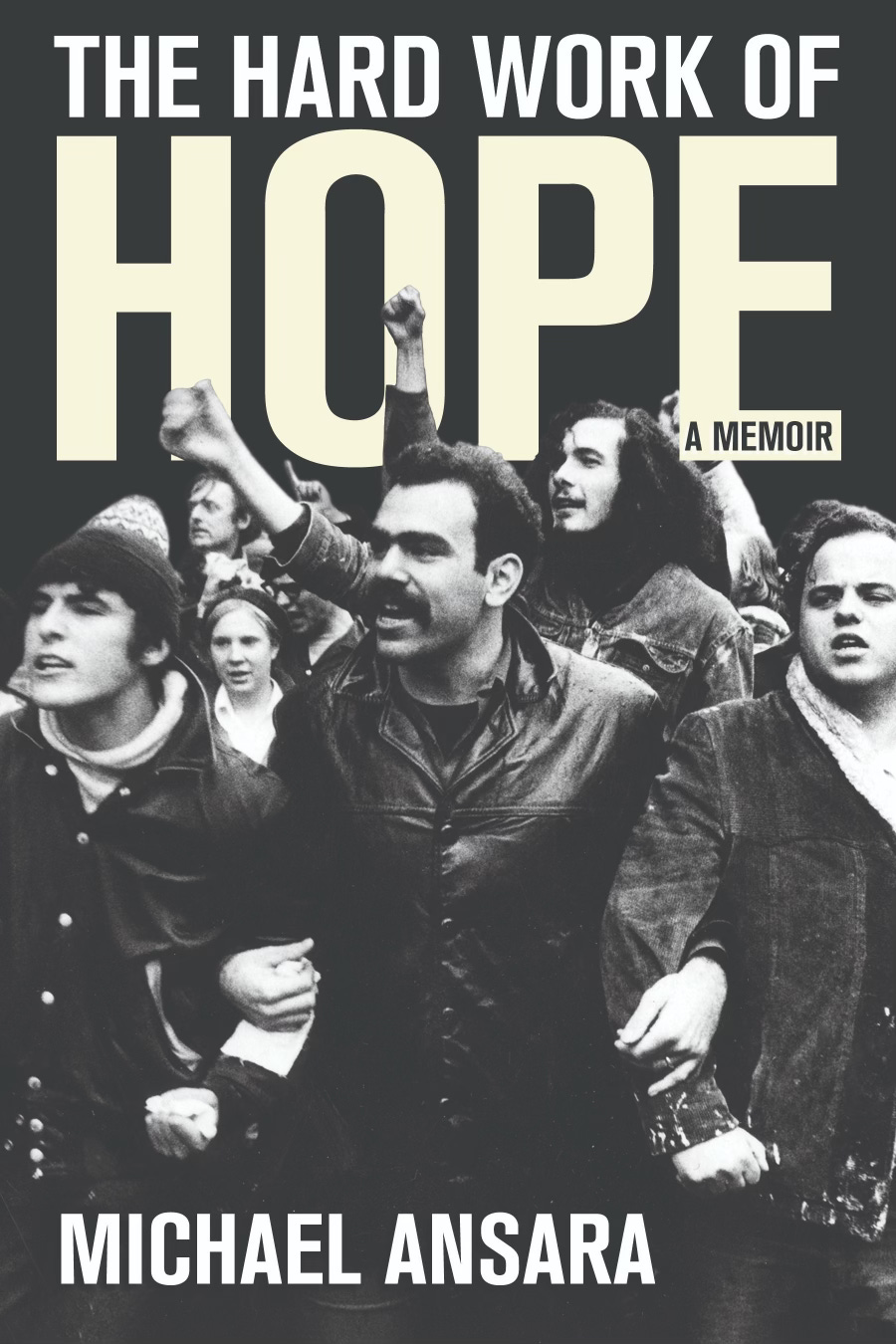

Michael Ansara’s The Hard Work of Hope: A Memoir will be published next month by Cornell University Press. I’m grateful to Michael for taking time to talk with me about his book, described by Todd Gitlin as “the most perceptive account I’ve ever read of the culture of organizing.”

In The Hard Work of Hope, I was struck by your relationship to the US and its ideals, especially as a young person—you describe, for example, a childhood “browsing in the American Heritage Book of the American Revolution or lost in a book of photographs from the Civil War.” Do you think there’s still a tradition of patriotic dissent among US activists? If not, is it worth trying to recultivate?

For the first generation of the New Left, our activism was born out of a love for the country, a peculiarly American optimism, and a profound belief in democracy. I think there is still a strand of protest and dissent that is patriotic, and that strand has grown in recent years. To fight effectively for significant reforms, one must possess a patriotic nationalism, a belief that your country is worth fighting for.

However, one legacy of the anti-Vietnam War movement and the end days of the New Left was a belief that America was irredeemable. The horror of that war, combined with the full realization of the deep-seated racism that permeated our history and our present, profoundly alienated many activists from the country. Over succeeding decades, the academic left, cut off from the actual practice of politics and organizing, focused more and more on the victims of America. The result was a rejection of any form of patriotism or nationalism. I was lucky. I was able to return to organizing and find a way back to a patriotism that could hold both the profound violence and wrongs of our history and the unique promise of American democracy. In a way I returned to the roots of my activism, a love of American history and the Declaration of Independence and a reasoned form of American exceptionalism that does not whitewash our history.

Another theme from your book that leapt out at me was the use of technology in activists’ communications work. (Maybe it’s because I’m a publisher, but I loved the mention of “a distribution system that can get a mimeographed leaflet into the hands of virtually every Black family within forty-eight hours.”) There’ve been big changes in how people alert one another to opportunities for political engagement, of course, especially with the onset of the digital era. Do you think those shifts have had an effect on the nature of activism?

When I re-lived the organizing of my past, I was struck by how we were able to communicate without computers, email, the internet, cell phones, social media, and Zoom. We did it primarily by harnessing the power of people to reach out to others. I do remember when at Fair Share, an economic justice organization, we first deployed fax machines. They seemed so revolutionary—within minutes we could move data or graphics from one end of the state to the other.

Certainly, the rise of digital tools has transformed communications. Today anyone can hold a meeting with people from all over the country on Zoom. Or send texts and reach thousands of people in seconds. Communication has been transformed. And to the degree that activism requires communication, it too has been transformed. However, I am not convinced that there has been a corresponding transformation for the good of organizing.

While I use all the digital tools for the work that I am now doing, I worry that people think signing a petition online is organizing. It is not. It is communicating and collecting names, but it is only the very lowest rung on a ladder of engagement.

Much of your book is set in and around higher education, a realm that’s navigating especially acute political challenges at the moment. Harvard, which you attended and where you remain engaged, provides a prominent example of these challenges. Does your background as an activist shape your responses to current tumult in higher ed?

As I write these responses to your questions, I am helping a new organization, Crimson Courage, organize thousands of alumni to support Harvard’s refusal to bow to the Trump administration. While I am critical of many of Harvard’s policies both over the years and recently, the larger issue of resisting the authoritarian destruction of independent centers of critical thought must override all other concerns. Once we have saved universities we can return to the fights over their policies.

Of course, I bring my organizing perspective to this effort—and a willingness to use digital tools to reach thousands of Harvard alumni across the country and indeed the world. It is not lost on me how ironic it is that 50-plus years ago I led a strike against Harvard and now I am working to support the Harvard administration. But one must always be strategic. We are experiencing the greatest threat to American democracy since the Civil War. Nothing is more important than stopping the illegal and unconstitutional acts of the Trump regime. Because of Trump’s attacks, and Harvard’s eventual refusal to accede, supporting Harvard has become one element of the essential fight to preserve American democracy.

There’s a lot in your book about people you admire—some familiar, some less known. Can you say a little more about books you admire? What would you recommend to people reading this interview?

Lord there are so many books that should be read! I would recommend reading books about the sixties such as the late Todd Gitlin’s The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (probably because I think people should read anything by Todd). I think the best comprehensive book on the anti-Vietnam War movement is Tom Wells’s The War Within: America's Battle Over Vietnam. There are many great books on the civil rights movement, from Taylor Branch’s three books on America in the King years to memoirs by many activists to the new biography of John Lewis. One book that people may not have heard enough about is Thomas Rick’s Waging a Good War: A Military History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968. It is a fascinating look at the movement’s strategies and history by one of the preeminent American military historians.

People should read about the American labor movement in books such as John L. Lewis: A Biography by Melvyn Dubofsky and Warren Van Tine. They should read about the populists, for example in Lawrence Goodwyn’s The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America.

On organizing there are, of course, Saul Alinksy’s books, especially Rules for Radicals. And a new book on organizing by Marshall Ganz—People, Power, Change: Organizing for Democratic Renewal, along with another recent book by Deepak Bhargava and Stephanie Luce, Practical Radicals: Seven Strategies to Change the World. Perhaps most importantly there are new books coming out from the new generation of leaders such as Cristina Jiminez and her book Dreaming of Home: How We Turn Fear into Pride, Power, and Real Change.

There are so many books—I have just scratched the surface!

It was fascinating reading your description of working with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which now has such a mythology built around it. In your telling of the day-to-day work involved with SDS, it felt more down-to-earth, and somehow approachable. Does SDS feel like a historical outlier, or are there lessons to be drawn from it?

Young people and students have often played a crucial role in sparking political movements and social change. That has been true globally. Think of Tiananmen Square in China. The Arab Spring. The Maidan Revolution in Ukraine. Over and over, it was young people who first protested. In those countries where the revolts spread to a broader population, they were at least initially successful.

In America, here have been huge changes in the conditions of young people from the 1960s to today. In the sixties we were riding a demographic wave. We did not have suffocating student debts. The economy was booming. We felt confident that the future was ours to make. Today the opposite is largely true. Young people today are weighed down by legitimate economic anxiety, debts, and impossibly high costs of housing. The future they are looking at seems more dreadful than hopeful. So much, including much of the academic left, tells young people that they don’t have agency.

Still, perhaps overly optimistically shaped by my own experiences, I believe the young people of America will find their way to fight for their collective future. There are many brilliant young activists and organizers emerging from the gloom. I believe they will chart a path toward social and political change. It will not be like SDS. It will not be something that I can clearly imagine. It will be new and it will be theirs. I do believe that.

Finally, I wondered if you could say a little about your theory of change. “No one was changed in a single discussion,” you write, which stuck with me. What does change people’s minds?

At the core of my theory of change is that we need both social change and political change. They are interdependent but not identical. Social change has to do with how people think, their relationships to each other, and how they live their lives. We need profound social change. But that social change cannot and will not happen if we do not create political movements capable of electoral success, capable of creating majoritarian coalitions that can use the power of government to counter the extreme power of corporations and the insanely wealthy.

The great forces that shape our politics today are the extreme inequality of wealth, the power of the elites, the betrayal of working Americans by those elites, and, as always, the racial divide.

In pursuit of both social and political change, I believe organizing is essential. Organizing is different from mobilizing. As my friend Richard Rothstein wrote decades ago: “organizers organize organizations.” And in the process of building organizations, they can change how people think of themselves, their relationships to others, and to power. Organizations can become great schools of democracy.

Critical to my theory of change is the fervent belief that people can change. We are not immutably defined and limited by either our past experiences or our demographics. People can change. It is the work of organizers to create the experiences that change people. The challenge is to contest for power but to do so in a way that pre-figures the changes that we want. I believe in democracy. For democracy to work we need an organized, self-confident, and educated citizenry with the day-to-day skills of democracy and a deep ethos of democracy. Right now, we are seeing what happens when a very large percentage of the population has none of that. The answer has to be to struggle urgently to win political power but in a way that builds the muscles, skills, and belief in democracy.

This last paragraph is utterly vague, useless in :real life.

I was in CORE ,SDS, Progressive Labor Party, and later, the National Writers Union. Of all those organizations, SDS was the most free-wheeling, democratic, and BOLD. Our ovuduerall credo waths "Less Talk, More Action." I was and am also a lifetime freelance writer with a pioneering short story collection 'I Looked Over Jordan and Other Stories" one of the stories wa optioned by Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis for a show they had on PBS; Ruby did an adaptation of the story Crazy Hattie Enters The Ice Age, about one of the most common experiences in America, an worker's refusal to sign a biased annual work performance evaluation.

I worked in hospitals for seventeen years and was in two of the most liberal unions in the country, SEIU Local 250 in San Francisco and independent ttunion 1199 in New York City.

I was also involved while a student in SDS in the historic San Francisco State College student strike led by our Black Student Union and Third World Liberation front that in a mightly coalition of students, many teachers, and local commnity, won the first Black Studies depatment and an ENTIRE School of Ethnic Stuidies that sparked a tsunami of revolt and victory

One of the most positive movements in recent years has been has been the Black Lives Matters Movements which brought thousands of people out into the streets to demonsrate, and even pushed on through to some of the murdering police convicted.

I guess Im also tired of seeing a lot of straight white men from Michale Ansara to Todd Gitlin and Mike Albert who from South End Press to Z MAGAZINE TO PODCASTS give us from their weary rhetoric as leaders as to what's going on in the country. So they think changes in technology will change how movements are organized. Wow. What insight.

When areyou going to feature books by some of the Black Lives Movement leaders, the Standing Rock struggle that the media right left and underwrote /ignored and certainly didnt do an indepth intervews with the new young leaders. I have yet to see a single article or interview with Congressperson Ocasio about her speaking tour with Bernie Saunders and what issues and concerns the redstate thousands asked t