Talking with Arlie Russell Hochschild

Her book "Stolen Pride," out next month, is a study of Appalachia

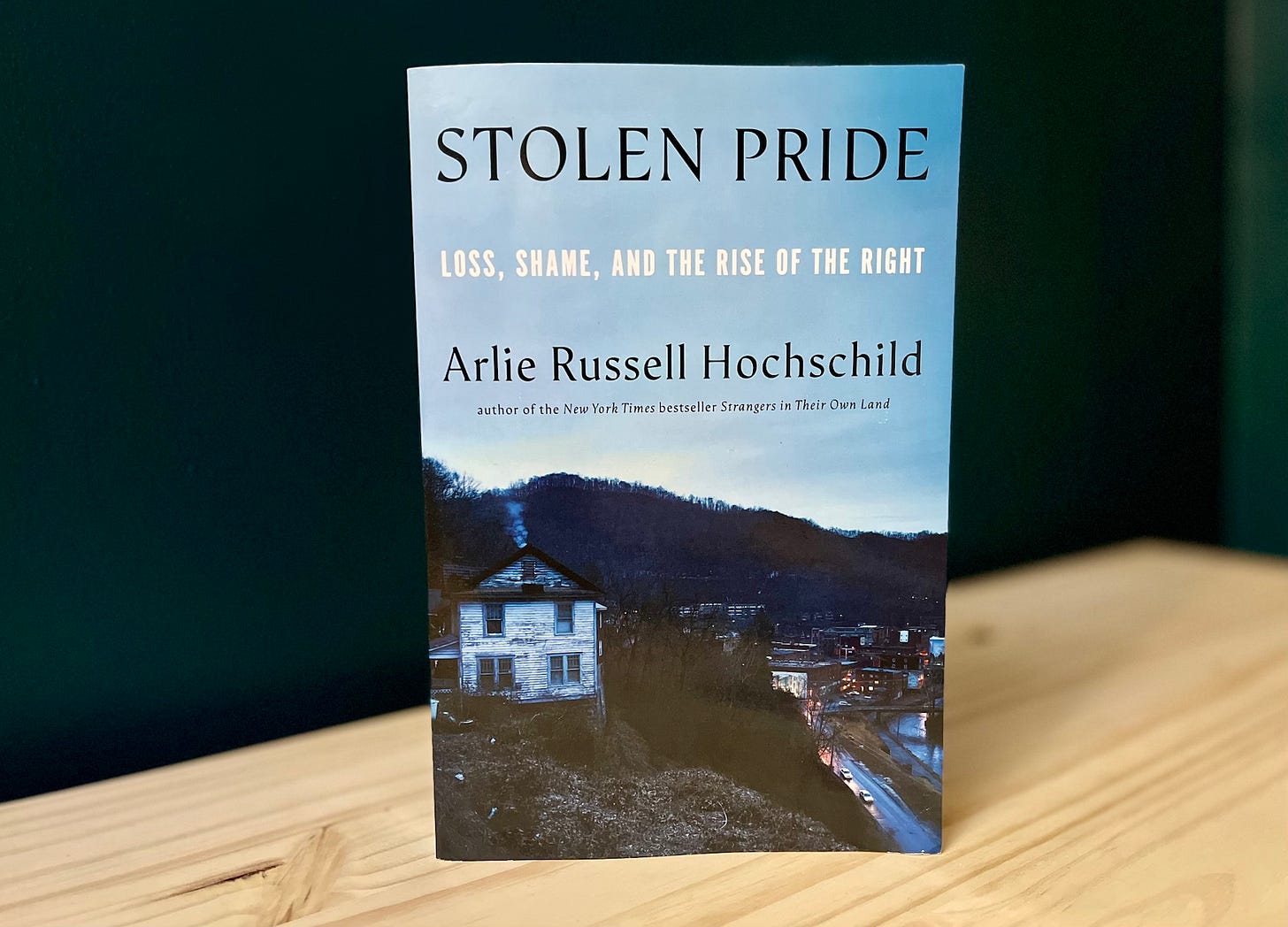

I was fortunate to get an early look at Arlie Russell Hochschild’s Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame, and the Rise of the Right, coming from The New Press in September—and even more fortunate that the author was willing to take time to respond to my questions about it. Hochschild is an award-winning sociologist at Berkeley whose interest in political identity leads her, in the new book, to conversations with the people of Pikeville, Kentucky. I’m pleased to report that the author’s tour takes her back to Kentucky for a stop at Carmichael’s Bookstore (a personal favorite) on September 12.

I enjoyed and learned from your new book Stolen Pride, which I read as someone who spent many years as a publisher in West Virginia, and came to the region from elsewhere. That background leads me to think there’s often a reasonable sensitivity in Appalachia about the experience of being interpreted by outsiders. In undertaking your project, were you self-aware about that point?

Yes, certainly. That’s why I took a long time to get to know people in this book: seven years. It’s why I tried my best to listen up and give full voice to what I was hearing. And once I got to know the people profiled in Stolen Pride, they shared with me that very “sensitivity” you mention. In fact, they talked to me about it—the experience of carrying around that sensitivity—and I wrote about it.

And as for who is looking at whom, the tables can turn. One man featured in this book, a Trump enthusiast, recently asked to interview me for his own podcast, turning the tables, so to speak. I told him “sure.” He took me around the hollers where he’d grown up. And I invited him to visit my family in Berkeley. He’s interested in renewable energy as a source of new jobs in eastern Kentucky; our son has a deep interest in that, so I thought it would be great to connect them. One young man featured in the book has already visited us.

Your career has now spanned half a century, and with each project you have sought closeness and intimacy with your subjects. In the case of Stolen Pride—which arrives at a very fraught political moment—what do you think you, as a university-based Californian, owe the people in rural or small-town Kentucky you write about?

What I feel I owe the people I write about? The act of deeply respectful listening, and I owe them the chance to get their own perspective accurately reflected.

What’s something you like about Pikeville? What do you think people in Berkeley could learn from it?

A lot. Pikeville is a little gem of a town, I loved the hanging flowers on Main Street, the annual Hillbilly Days Celebration, all the parades, a culture that feels both intimate and cosmopolitan. I found it open-spirited; one July 23 I sat down by myself at an outdoor café during a street fair, and got talking with some people who asked me what I was doing there, bought me a beer. They were very friendly and offered to be interviewed. Alas, I was winding things up and didn’t need more but I loved that, and regretted I hadn’t met them earlier.

In the realm of party politics, some observers have pointed to class dealignment—the Democrats’ shift to an increasingly professional base in certain sorts of urban and suburban enclaves, while less affluent voters (increasingly across racial categories) often vote for Republicans. I will acknowledge my own situatedness: moving from West Virginia to leafy Squirrel Hill in Pittsburgh has meant, among other things, a remarkable change in neighborhood yard signs. What do your experiences in Pikeville suggest about party politics and class?

Social class, and the pride and shame attached to one’s rises and falls in it, seems to me the elephant in the living room. Many on the liberal left seem class-blind. As Joan Williams argues in the forthcoming book Outclassed, class blindness is as important as race blindness. William Barber’s new book White Poverty turns to the need for cross-race focus on social class. I hope to contribute to that ribbon of thinking.

While we’re talking about party politics, I suppose it’s hard to avoid JD Vance. Obviously, Stolen Pride was written before he was selected as the Republican candidate for vice president, but it’s also worth noting that your last book, Strangers In Their Own Land, appeared with Hillbilly Elegy and others on a 2016 New York Times list, “6 Books to Help Understand Trump’s Win.” Do you think your experiences in Pikeville can shed light on Vance’s ideas (or his book)?

While Vance emerged as a Republican vice-presidential candidate long after my work in eastern Kentucky, you could read the book as an answer to Vance. Many of the people featured in my book had to deal with similarly tough situations but came out with very different world views.

I want to close by asking you to talk about someone you met in Pikeville who might confound easy assumptions about Appalachian Kentucky. Who’s a surprising person in your book?

I met a 38-year-old TikTok artist with a long black ponytail who grew up in a Martin County trailer park about 90 miles from where Vance’s grandparents lived. He described himself as a political independent whose identity defied the usual pigeonholes. As he told me, “I feel like many on both the right and left don’t get people like me. I’m poor. I’m white and disabled and I’ve always lived here, okay? But I’m not racist or anti-immigrant and I feel like Donald Trump probably mistakes me for someone else. In 2016 he came to Appalachia to appeal to people like he thinks I am. In fact, Trump wants the whole country to feel like he thinks I feel—i.e., to make them feel like poor whites. But I don’t feel like he thinks I do.” It wasn’t just Donald Trump whom he felt didn’t get him. He felt neither political party got him. He saw tax cuts and retribution on the Republican side and a preoccupation with identity politics on the Democratic side. The reader can get to know more about him in Chapter 8; he’s there.

Pikeville, KY, sounds a lot like Meadville, PA: both are home to a small liberal arts college. Guessing some themes you’d find in Matt Ferrence’s book resonate here, too.