Speculative nonfiction

My Q&A with Michael Lowenthal, author of "Place Envy"

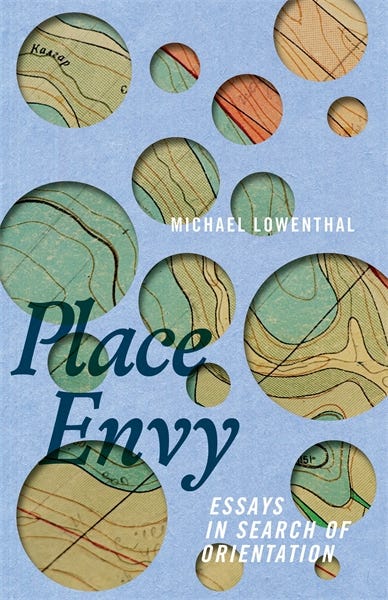

I was pleased to get an early look at Place Envy: Essays in Search of Orientation, coming in February from Ohio State University Press, and to talk with author Michael Lowenthal about his book. It lives up to the early buzz (“an act of moral and emotional cartography,” says Kirkus), and I’d encourage readers to watch for bookstore and festival events this winter and spring. Thanks to Michael for the great conversation.

Without giving away too much, tell me a little about Peter, the figure who sets your book in motion.

Peter was my half uncle—my grandfather’s first son, from a marriage that predated his marriage to my grandmother. I had never heard of him, and had no idea he’d existed, until my grandfather died and his obituary mentioned Peter’s name, saying he had died in the Holocaust. (My grandparents were German Jewish refugees who fled Europe in 1939.) When I learned of Peter, I was fourteen; my already emotionally distant father had recently moved across the country to California, and I yearned for male mentor figures; and I was starting to figure out, through great shame and confusion, that I was gay. All of which contributed to my projecting onto Peter all sorts of feelings and idealized fantasies. Since then, Peter has acted as a kind of talisman throughout my writing life, inspiring parts of my first novel, way back in 1998, and now serving as the spark for my memoir—which explores the same questions of belonging and identity that, when I was a teenager, made me gravitate toward this uncle figure who arrived out of nowhere.

I was struck by a passage involving one family member, rescued by the Soviets in the last days of the Holocaust. You imagine possible details about her liberation, and then catch yourself: “There I went again, spinning up a story. Soon, I wouldn’t have to; I would have the facts.” This feels like a key dynamic in the study of Jewish heritage and perhaps immigrant and diaspora studies more generally—the relationship among stories, myth, imagination, and the hunt across places and languages for what’s recoverable. What’s your sense of that dynamic as it’s animated in your book? Is there a risk of losing something through detective work?

That’s such an important and provocative set of questions, and I’m glad you see them as potentially having relevance to other diaspora heritages too. As you intuited from the example you cite—and as you could probably guess from the fact that my uncle Peter inspired both a novel and a memoir—I’ve long felt torn between wanting to uncover the true history and wanting to imagine my own version.

On one hand, especially in an era of increasing denial of the Holocaust—and of historical truth more generally—I feel a duty to preserve and honor the recoverable facts. On the other hand, I can sometimes feel hemmed in by the facts, which, though this might sound crass or irresponsible, can get in the way of a dramatic narrative. And I’ve always believed that narrative is what most moves us and provokes our empathy. Historical facts sometimes invite us to separate ourselves from events and to feel that the past is, well, past: Oh, that’s what happened to those people, and it’s all finished. Whereas narrative and myth invite us more directly to imagine ourselves into an ongoing story.

I know that when I finally learned the facts of what happened to Peter, I felt both satisfied and, in an unsettling and maybe shameful way, let down—because then I had to give up the myths I’d built up around him. And the risk was that I would consequently feel less, not more, connected to the heritage he represents.

The final long essay in Place Envy is also animated by these dynamics. I get wrapped up in detective work trying to uncover the fates of two other long-lost relatives of mine, a great-great-uncle and cousin who died only a couple of days apart, as young men, in 1862, and who I have reason to suspect (hope?) might have been queer predecessors in my family. The upshot of the detective work is that the “truth” is unresolved and probably unresolvable. At first, I worried that this ruined the story, and I considered scrapping it. But eventually I decided that the open-endedness actually made the story, because it forced me to focus on my own investment in this heritage. I had to ask myself why I cared, and if/how my own life might change depending on what facts might emerge, or whether what mattered the most was my coming to understand the significance of the search.

I imagined these relatives’ fates, as I did with Peter, in a way that I guess you could classify as “speculative nonfiction.” Which is maybe the best of both worlds? It relies on facts and truth, and clearly acknowledges when it departs from them, but allows room for imagination and, I hope, greater emotional investment.

I wanted to ask about the “place envy” in your title, particularly since you evoke places (the rural Pennsylvania of the Amish, for instance, or the Isle of Lewis in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides) so vividly. Can you say a little about your places? As a Pittsburgher I’m especially interested in your connection with this city.

As I say in the book with regard to “place envy,” I grew up in places (Peru, New Jersey, Maryland) where my family had no past or connection, and I envied folks who were nth-generation residents of a certain town or who spoke with a strong regional accent. I saw geography as a kind of shortcut to the sense of belonging I yearned for—even though, I now understand, there are of course nth-generation residents of certain places who feel plenty alienated, sometimes precisely because they don’t conform to the mores of those places.

Place envy has inspired my travels—I’ve ventured to many different countries and communities, hoping to feel a connection—but I think it also explains why I’ve been pretty rooted, or maybe even stuck, in my home places. Once I establish a connection, I want to go deep and become as much of a local as I can (even as I struggle with questions about who gets to be deemed a local, and even as I’m wary of the nativism and exclusion that can be attached to these questions). I moved to Boston after college, and it’s where I’ve now lived for thirty-two years: more than ten years in the same rented apartment and now twenty years in my house. Boston is the place where my mother’s side of the family has a long connection; as a lifelong Red Sox fan, I cherish a 1955 newspaper article I have that celebrates my great-grandfather’s attendance at his sixty-first Red Sox home opener game—his first was in 1887.

I also have a deep connection to Cape Cod, where my father was born and where he’s had a house for some fifty years. Going back to the same beach, year after year, and feeling what has changed and what’s remained, is a kind of exploration that can be as eye-opening as jetting off to the Hebrides or wherever.

I thought I was done having home places, and that by this point in my life, it would be impossible for any new place to feel anything but new. But about a decade ago I started dating my partner, who lives in Pittsburgh, where he grew up and where his family is still deeply rooted. It has been the great surprise and privilege of my midlife to fall in love with Pittsburgh—the Pittsburgh that exists beyond clichés about saying “Yinz” or eating Primanti’s sandwiches. I love learning the rivers and hills and getting a sense of how they shape the human neighborhoods that have grown up around them. I love having opinions about which Lenten fish fry or Western PA county-fair demolition derby is the best. And I love the ways I’m challenged by being a citizen and neighbor in a purple part of the country, after so many decades in deep-blue Massachusetts.

When I was submitting the final manuscript of Place Envy, I changed my author bio from “lives in Boston” to “lives in Boston and Pittsburgh.” It felt true and, for me, profound. I was struck by what great fortune it is to have more than one place that feels like home.

How do you see yourself in relation to the tradition of Jewish writing? Are there Jewish authors at work now whose books you’d particularly recommend?

Especially at the start of my writing life, I didn’t spend much time thinking about “Jewish writing” as being distinct from writing in general—maybe because so many of the great contemporary Jewish writers were the same as the so-called Great American Novelists (Roth, Bellow, Malamud). More recently, I’ve come to appreciate certain qualities that are arguably vital to Jewish writing, many of which I think overlap with the literature of other diasporic and immigrant and marginalized communities, including queer folks: a commitment to the inseparability of tragedy and comedy, a thin line between irony and earnestness, a bone-deep distrust of authority (that, in the case of Jewish writing, gets tangled up with a religious tradition obsessed with questions of authority).

The Jewish writers I’d think of to recommend are mostly those whose Jewishness might be less central to their content than to their style or voice. Deborah Eisenberg, Bernard Cooper, Grace Paley. I’m also lucky to be friends with some writers whose work is brilliantly rooted in questions of Jewish heritage and history: Rachel Kadish, Elizabeth Graver, Benjamin Taylor.

My favorite work of Jewish writing is probably Linda Pastan’s poem “A Short History of Judaic Thought in the Twentieth Century,” which, in little more than fifty words, captures the essence of Jewishness. Look it up!

Finally, as a longtime publishing worker employed mostly by university presses, I’m interested in how you came to Ohio State University Press. Can you tell me about the experience?

I’ve published books with big mainstream New York publishers (Dutton, Houghton Mifflin) as well as smaller, independent presses (Graywolf, University of Wisconsin Press). I’m super proud of Place Envy, which I think contains some of my best writing, but I also know what it is, in industry terms: a memoir-in-essays by a literary writer who, after five other books, still hasn’t hit the bestseller list. So I made what felt like a clear-eyed choice to spare myself the time, effort, and likely disappointment of querying agents, trying to line up a Big Five publisher, etc. Instead, I decided to represent myself, and I started by submitting the manuscript to the three indie presses that were my top choices. One of the three was OSUP, because I appreciated their commitment to publishing creative nonfiction generally and essays specifically; because I had a connection with Joy Castro, the editor of their Machete series; and also especially because of my admiration for the editor-in-chief, Kristen Elias Rowley. During Covid, Kristen gave a Zoom talk to the MFA program where I was on faculty, and I loved everything she said. Plus, I found out she’d been mentored at the University of Nebraska Press by my friend Ladette Randolph (former editor of Ploughshares). The stars just seemed to align, or at least I hoped they would. I submitted, and they accepted! Later, Kristen gave me a key piece of editorial advice that elevated the book. I’ve been around publishing long enough to know what a privilege it is to have an editor who actually edits!

The rest of the OSUP team has also been stellar. Great book designers who welcomed my input in the cover design. Meticulous production team. Passionate publicist.

My very first “real” job after college was at the late, lamented University Press of New England—as editorial assistant, then editor. The work I was proudest of involved “rescuing” writers who had been dropped by New York publishers. I published novels by Chris Bohjalian and Ernest Hebert that those publishers had turned down. So it feels like a kind of homecoming to be published by a great university press like OSUP. I feel grateful and lucky!

I didn't know Michael had a new book. I'm looking forward to getting my hands on this.