I’ve been fortunate to share occasional perspective from Jeremy Wang-Iverson, a publishing professional with whom I’ve collaborated in many capacities. One of our most successful partnerships—publishing and raising awareness of Deesha Philyaw’s story collection The Secret Lives of Church Ladies—got some good news last week when it was named by Kirkus Reviews to their list of the best books published (so far) this century. Congrats to the author, but also to Jeremy, who’s done so much to help propel Deesha’s book into public conversations.

I’m grateful for Jeremy’s report from his home base in Spain, which arrives at a moment when transnational exchanges deserve special celebration. Here’s Jeremy:

I had the opportunity to work with the talented editor and critic Sophia Stewart on a new piece for Publishers Weekly on Spanish publishing. This article is a profile of the publisher Sexto Piso, which has published over 600 books since its founding in 2002. Eighty percent of its titles are translated into Spanish, with many authors whose work will be familiar to readers of Book Work.

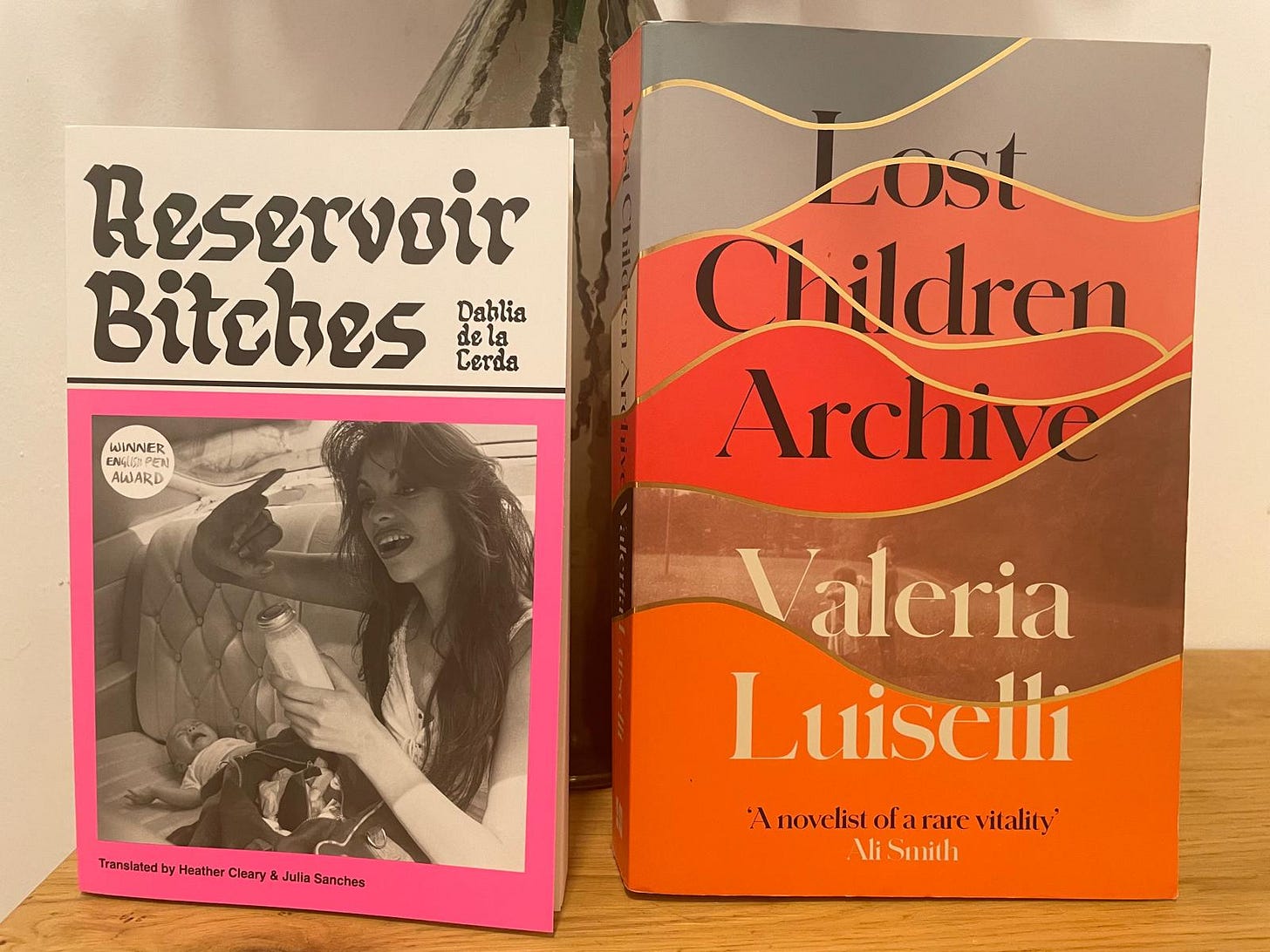

My PW article focuses on Sexto Piso’s program to bring books into Spanish, but I also wanted to say a word about the publication of Spanish and Latin American authors in English, and Sexto Piso’s success here as well. I’ll mention three of their authors. Dahlia de la Cerda wrote the short story collection Reservoir Bitches, translated by Julia Sanches and Heather Cleary, which was recently longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize. Brenda Navarro’s A Mouthful of Ash, translated by Megan McDowell, is forthcoming from Liveright and is being adapted into a film, co-written by Diego Rabasa, one of Sexto Piso’s editors. Valeria Luiselli is also published by Sexto Piso, including her most recent novel Lost Children Archive, which she wrote in English and translated into Spanish with Daniel Saldaña Paris.

Just as Sexto Piso has played a key role as an independent press to bring certain American and British authors to Spanish readers, many independent publishers in the anglophone world—such as Coffee House Press (Luiselli’s first publisher) and Feminist Press (which is publishing Dahlia de la Cerda)—have led the way in recent years to bring Spanish and Latin American literature in translation to readers in English.

“Corporate houses tend to try to copy successes,” said New Directions publisher Barbara Epler in a recent interview with Publishers Weekly. “The independents usually first locate the really new voices.” Indeed, Epler was first to publish Roberto Bolaño in English, when New Directions published the Chris Andrews translation of By Night in Chile in 2003.

Sixty years ago, with the boom latinoamericano—as Angelo Hernandez Sias notes in a recent article in The Drift—many of the larger American publishers were championing work in Spanish. But that was an era prior to corporate consolidation. “The so-called boom’s canon—much of it now out of print or in the midst of small-press resuscitation—by and large came out with major US publishers: One Hundred Years of Solitude with Harper & Row, Hopscotch with Pantheon, Paradiso with Farrar, Straus, The Obscene Bird of Night with Knopf.” Certainly these were much larger operations than the publishers focusing their lists on translations now, such as Open Letter Books or Two Lines Press, both of which are set up as non-profits.

Awards in the US and the UK such as the Man Booker International Prize are also very important for the promotion of translated literature, and the National Book Awards has a category for translated literature as well. The Cercador Prize is a new initiative from American booksellers to recognize translated literature—last year Agustín Fernández Mallo's The Book of All Loves, translated by Thomas Bunstead, was the winner.

“The Book of All Loves takes great risks, and pulls off its grand experiment with grace,” wrote Cercador co-founder Spencer Ruchti, who also works as the events manager at Third Place Books in Seattle, Washington. “Eager to get this book into the hands of our customers and see what conversations emerge.”