I suspect a lot of publishing professionals remember a perfect publishing day. Here’s mine: I met the literary agent Danielle Chiotti in Pittsburgh in 2019, a conversation that resulted in my signing Deesha Philyaw’s book The Secret Lives of Church Ladies for West Virginia University Press. Visits to Pittsburgh from Morgantown (where I then lived) always felt like a dose of professional adrenaline, but that trip was especially dense with perks—the same day I met Danielle at the coffeeshop in the delightfully named Detective Building, I also saw Olivier Assayas’s publishing movie Non-Fiction at the Manor, had lunch at an honest-to-god French restaurant, and stopped in the (now defunct) Classic Lines bookstore. Big-city stuff all around, and the start of a trajectory that led to the National Book Awards.

I could go on and on about the book scene in Pittsburgh. What I want to focus on from that day’s initial conversation about Deesha’s book, though, is the insider-y publishing phenomenon of trim—a book’s physical dimensions, specifically height and width. Anyone charged with signing books has a mental checklist about how and whether they can make a prospective project work, and from the very first conversation about Secret Lives I was wondering (among other things) what the book would look like, especially since the manuscript was short. In our industry most sales (about 90% for WVU, at least as of a few months ago when I left) are print rather than digital, and readers want a satisfying print object. They also want a price that feels appropriate for the object they’re buying, which gets tricky for short books. While a short book is cheaper to print than a long one, it’s only so much cheaper, plus a lot of a publisher’s costs don’t have to do with printing and may be equally high for pretty much any book, regardless of the length. So there’s only so low most publishers can responsibly go with a book’s price, which is one of many incentives not to publish books that seem physically insubstantial and conjure bargain-bin prices.

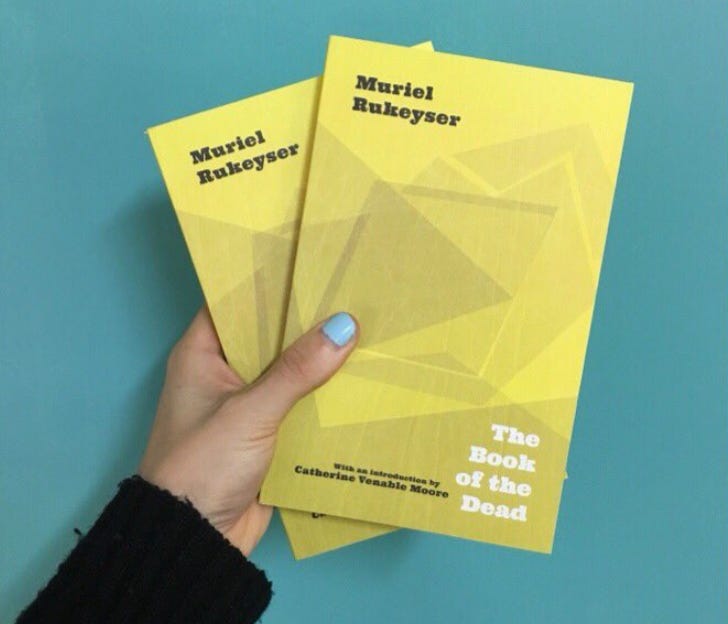

Fortunately we had recently published an edition of Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead, a poetry cycle with an introductory essay and a smattering of photos and other apparatus. Set in West Virginia, it was a perfect project for us, except that it was so short (much shorter than Secret Lives) that it risked seeming like a pamphlet. We settled early on paperback, always our preferred format—cheaper to manufacture, and easier to keep in stock because it can be reprinted faster (a consideration that became especially prominent a little later, with the pandemic shutdowns and supply-chain crises). You can put flaps on paperback, and with The Book of the Dead we did, making a more beautiful object that felt like it supported an $18 price tag. We also settled on a loose, easy-to-read interior design that gave the book some heft without (I hope) seeming like we were padding it.

Most important of all, though, my colleagues and I settled on an unusual trim: 4.72 x 7.48 inches. Small and elegant, the 4.72 x 7.48 trim works with almost every printer (again, a consideration that become huge during the pandemic). And it yields a satisfying package—a book you want to hold in your hand.

Within minutes of first considering Secret Lives, I latched onto The Book of the Dead’s package as a way we might match the manuscript’s enormously appealing qualities with an appropriate publishing strategy. I could already see Secret Lives as a thing, because my colleagues and I had worked through similar challenges on a previous project, gauged the reaction of booksellers and others, and arrived at applicable know-how for our toolkit.

A lot has been written about the lessons to be drawn from the publishing history of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies. There are certainly bigger, more important stories embedded in the book’s success—about race, publishing industry consolidation, and more. Those systemic phenomena are obviously worthy of study and comment. To the extent West Virginia’s tiny team helped address these large issues with Deesha’s breakout book, though, our efforts were enabled by pragmatic interventions like knowing how to publish a charismatic paperback original under two hundred pages. That quotidian stuff is part of publishing’s expertise and its labor—and I don’t think it’s possible to start solving the big problems without celebrating (and investing in) this specialized work.

I’ll wrap up with news of the strike at children’s publisher Scholastic. It’s part of a recent wave of labor activism in book publishing.

Books-as-objects is too little discussed, outside of the realm of people who have a professional interest in it. Yet as the world becomes more digital, the competitiveness of books will depend increasingly on their appeal in the hand and to the eye. More posts of this type would be appreciated.